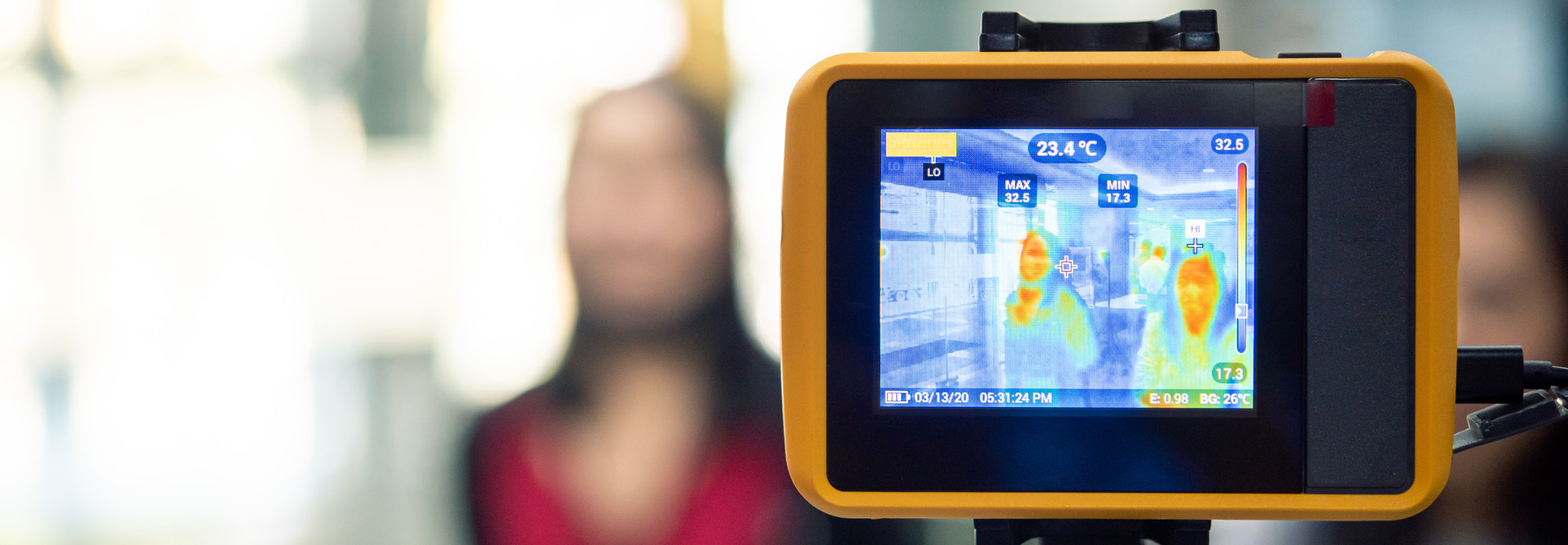

As healthcare organizations prepare to welcome more patients back to public spaces while the COVID-19 pandemic continues, some facility managers are deploying thermal cameras in entryways as an added safety measure.

The goal: to quickly screen each visitor to detect if he or she may have a high temperature, and to route them to medical care if signs of trouble are detected.

Applied to a single spot on a person’s skin, the infrared technology can produce a rapid reading — a prescreening measure used in buildings such as hospitals and schools. Individuals found to have an elevated temperature should be retested with a medical-grade thermometer, experts say.

“We see the thermal camera as the initial screening, for processing people as they enter a building,” Peter Frank, an education product manager at Ergotron, recently told EdTech: Focus on Higher Education, a sister CDW publication. “These devices don’t detect fever; they just measure that surface skin temperature.”

To get a reliable surface reading, most thermal cameras must calibrate against a “black body,” an accessory that is usually sold with the camera. The camera indicates the difference between the subject’s and the black body’s predetermined temperature.

READ MORE: Discover three trends that will influence healthcare as staff return to work.

Some scanners, however, can self-calibrate, and the distance that the various tools must be positioned from a subject will vary. Other environmental factors must also be considered when setting up a screening station.

Overall, thermal imaging generally has been shown to accurately measure surface skin temperature without being physically close to the person, according to the Food and Drug Administration. It cannot detect other symptoms or definitively confirm COVID-19, as some infected people may be asymptomatic.

How Hospitals Use Thermal Camera Technology to Evaluate Visitors

At Memorial Hermann-Texas Medical Center, four thermal cameras have been installed at two of the Houston system’s biggest facilities where nurses used to physically take the temperature of each visitor — a slow and time-consuming process.

“In between each temperature, they had to sanitize the thermometers,” a hospital project manager told the Memorial-Hermann blog in May. “Just think about 1,000 people and the lines. The longer the line, the less likely that people are going to be 6 feet apart … we had to improve the flow.”

Rush University Medical Center in Chicago installed infrared temperature screening stations in March. People entering the building now follow directions on a tablet to position their head correctly, then wait for a green check or red cross symbol to indicate the results of their thermal scan.

The system has caught a few people who, when screened by staff, had other symptoms suggesting infection, such as chills, Dr. Jordan Dale, a Rush physician and acting chief medical informatics officer, explained in an interview with Wired.

“If we can prevent just one febrile person from coming onsite and spreading the virus inside the hospital, that has a huge impact,” he says.

At the start of the pandemic, Tampa General Hospital introduced an AI-powered screening system that uses camera-embedded devices stationed at the hospital’s six visitor entrances. Together, the tools can analyze facial attributes such as sweating and discoloration as well as data from a thermal scan, The Wall Street Journal reports.

In many cases, the technology’s resulting efficiencies can reduce the number of employees handling fever-detection duties and direct them to other critical tasks.

Deployment of a thermal imaging camera at Central Vermont Medical Center in Berlin, Vt., “greatly decreases the time it takes for [visitors] to enter, eliminates the need to remove their masks, and decreases the time they spend in close proximity to our staff, which keeps everyone safer,” Robert Patterson, the hospital’s vice president of human resources and clinical operations, told Vermont Business Magazine in June.

Pros and Cons of Infrared Thermal Cameras in a Healthcare Setting

Despite their benefits, the scanners aren’t foolproof, and their effectiveness can hinge on external factors.

A patient wearing a hat or head scarf, for instance, could have a higher body temperature, as could someone who just exercised or took a warm shower. Someone with a fever coming in from the cold may also receive an inaccurate read.

Moreover, skin temperature is usually lower than a temperature measured orally, the FDA notes, so thermal imaging systems must be adjusted properly. And the spaces where scans take place should be void of conditions that can unintentionally affect outcomes: no reflective backgrounds, drafts, strong lighting or radiant heat sources.

Precision also matters. Research suggests the region of the face that best reflects core temperature is the inner corner of the eye, a trio professors from Deakin University in Australia wrote in May in a post for The Conversation. This is a very small target, they note, so a screened individual must be very close, directly facing the camera.

As the technology becomes more commonplace, organizations must consider privacy concerns that could result from thermal scanners. Efforts to communicate the necessity, function and data protection measures behind these tools can be a critical step toward compliance and trust.