What Is an Otoscope?

An otoscope is a common medical instrument that allows doctors to look into tight areas, generally on the human head, most commonly the ear. If you ever get the tip of a cotton swab stuck in your ear (be careful!), an otoscope will come in handy by making it easy for the specialist to examine the ear up close, so they can figure out what they need to do next.

An otoscope has two parts: the handheld device itself, which contains a lens and a light source; and a plastic attachment called a speculum, which goes near or inside the ear, allowing for visibility deep inside the ear’s narrow cavities. But otoscopes aren’t limited to the ear — they’re also handy for analyzing the interior of other areas, such as the nose and throat.

Modern versions of the device can illuminate dark areas through the use of a penlight, making visibility into even the tightest corners possible.

It seems so simple today, but the basis for this fundamental device goes back hundreds of years, through generations of innovations.

Who Invented the Otoscope (and Ear Speculum)?

The word “speculum” is Latin for “mirror,” but it came to describe the tools doctors would use to look into visible body parts like the ear — and before the otoscope, the device was simply known as an ear speculum. The person most frequently credited with the earliest description of the ear speculum is broadly considered an innovator in the medical field. Guy de Chauliac, creator of the Chirurgia magna, an early document on surgery, is generally cited as the first to describe the concept of the aural and nasal speculum in 1363.

RELATED: A simple design keeps manual blood pressure monitors in the mix.

As you may guess from the timing, de Chauliac came to prominence at a difficult time in world history, in the middle of a pandemic of the plague known as the Black Death, which devastated Europe during the mid-14th century. His work during this time developed his knowledge of surgical procedures that later came to shape the medical profession.

One of those innovations was the speculum. As portrayed in illustrations in Laurent Jobert’s 16th-century book Annotations sur Toute la Chirurgie de Mr. Guy de Chauliac, this early type of speculum relied on a duckbill-shaped instrument that expanded the size of the orifice to allow for better visibility.

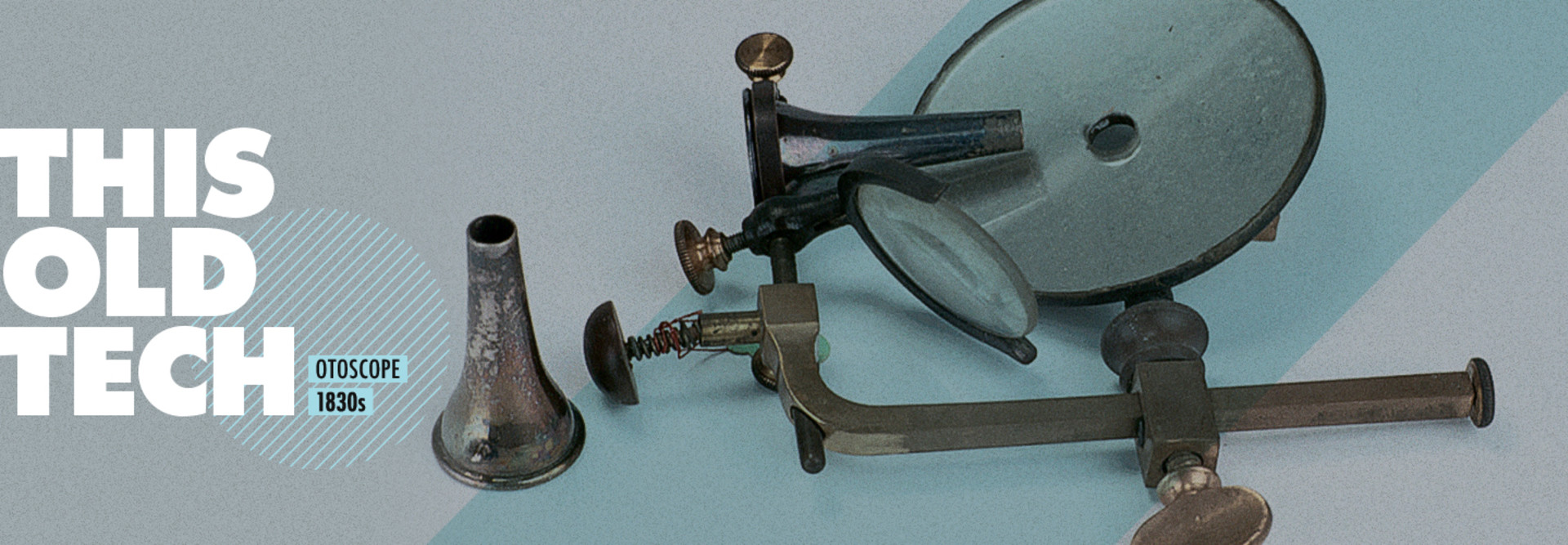

While de Chauliac was first to describe the speculum, it would be about 300 years before another medical innovator actually created one, in the 17th century. Wilhelm Fabry, considered the father of German surgery, developed an aural speculum. Despite the small size of the human ear, the aural speculum (at left in the picture above) is shown with a human hand for scale, suggesting quite a large size.

A more compact speculum, developed by French master cutler Jean-Jacques Perret (who, notably, also invented the modern safety razor), was highlighted in his catalogs of surgical instruments.

In the 19th century, medical technology for the ear began to mature. Key to this evolution was Wilhelm Kramer, who is believed to be one of the first medical professionals to specialize in otology, the study of the ear.

In his 1863 book The Aural Surgery of the Present Day, Kramer described his aural speculum, which had a narrow funnel at the end, as one he had used thousands of times over a 30-year period.

“Any defects it may appear to possess when in use result simply from a want of dexterity on the part of the operator, who introduces or opens it with too heavy a hand,” he wrote.

The initial form of the otoscope came about in the 1830s thanks to Jean-Pierre Bonnafont, a French inventor who found that by directing a light source into the ear using a mirror, he could better see into the ear canal. Bonnafont’s work, called the “speculum autostatique,” benefited from the improvements in modern microscopes during this period. But there was still room for improvement.

Further advances came from British military doctor John Brunton, who improved on the otoscope by creating a way to allow more light in. In an 1865 edition of The Lancet, Brunton said he was inspired by the challenge of seeing inside a patient’s ear.

In the spring of 1861, while examining a patient’s ears with the ordinary aural instruments, two serious difficulties arose to me in forming a correct diagnosis with such instruments—viz.: 1. That the observer’s head very greatly obstructed the light; 2. That the eye could not get near enough the object to permit of minute examination, and more so if sunlight instead of artificial light was used.

The speculum itself, which had evolved into a conical shape, also improved over this period. German Arthur Hartmann — who also invented alligator forceps for removing foreign objects from the human body — developed a simpler cylindrical shape for the ear speculum that is still used today.

These two parts, working in tandem, were further improved upon in the decades since Hartmann, with the addition of artificial light sources and a simple handle. The otoscope soon became a common instrument for specialists and family doctors alike. Removable ear speculums are still in use today, though they’re often made of plastic, rather than metal or rubber as they might have been back then.

MORE FROM HEALTHTECH: Forward-looking medical professionals leverage 3D printing.

Why Does the Otoscope Still Matter?

John Brunton’s frustration of trying to get enough light to see inside a patient’s ear canal is no longer a problem with modern otoscopic equipment; vendors such as Avizia have added significant video capabilities in recent years.

And that technology — which is all about extending the doctor’s view just a little bit farther — is starting to reach into areas that in the past could not have been examined without surgery.

Recently, the academic publication JAMA Otolaryngology – Head & Neck Surgery reported the results of a study that found videoscopes, used with smartphones, were becoming practical in telehealth settings, allowing patients to share videos of ear, nose and throat conditions with their doctors through the cloud.

In fact, part of what makes this technology possible is how inexpensive it has become — 70 percent of patients were willing to pay $35 to buy a personal digital videoscope, according to the JAMA study. Given that it was once impossible to see inside the ear canal at all, that’s a lot of progress in just a few hundred years.