Telemedicine Technology Helps Doctors Treat Patients, No Matter the Distance

Shortly after a 25-year-old man with flu-like symptoms and difficulty breathing arrived at Union Hospital — a small, rural facility in Cecil County, Md. — two physicians scanned his vital signs and noticed a low oxygen intake. They also saw blood coming out of his lungs.

But the doctors weren’t in the same room with him, or even in the same hospital. In fact, they were huddled in front of eight monitors and several computers 60 miles away at the University of Maryland Medical System (UMMS).

“It was easy to tell the patient was in deep trouble,” says Dr. Marc Zubrow, vice president of telemedicine at UMMS, who was on duty as part of a telemedicine program and quickly ordered a helicopter to transport the patient to the University of Maryland Medical Center (UMMC).

There, doctors put the patient on an artificial lung machine to help him breathe and gave him antibiotics to fend off a bacterial infection. The man is alive today thanks in large part to the telemedicine program, which was created to address a national shortage of critical care physicians.

“We work closely with the bedside teams, and jointly we are saving lives,” Zubrow says.

UMMC’s telemedicine program allows physicians to use encrypted, high-definition video and other technology to monitor intensive care unit patients and deliver high-quality healthcare during overnight hours and weekends at 11 remote, mostly rural hospitals.

Telemedicine services, from video and email consultations to in-home monitoring of patients through Bluetooth devices, help providers make healthcare more accessible and affordable to patients. They bridge gaps in care by allowing rural physicians and patients to consult with specialists at larger, better-equipped urban hospitals, and provide a learning platform for primary care doctors determined to deliver better care to their patients.

SIGN UP: Get more news from the HealthTech newsletter in your inbox every two weeks

Tapping Telemedicine as a Teaching Tool

Sixty-six rural hospitals have closed since 2010, and 77 percent of rural U.S. counties in 2016 were part of what are deemed “primary care health professional shortage areas,” according to the National Rural Health Association.

“Telemedicine is a critical means of providing specialty and emergency treatment for rural Americans,” says Lynne Dunbrack, research vice president for IDC Health Insights. “It means they don’t have to travel hundreds of miles to receive care.” It also allows doctors to better share knowledge with their peers. Five years ago, Dr. Evan Klass of the University of Nevada, Reno School of Medicine (UNR Med) deployed an initiative that connects university-based specialists with primary care clinicians in rural areas throughout Nevada.

Project ECHO (Extension for Community Healthcare Outcomes) — the brainchild of Dr. Sanjeev Arora in New Mexico — represents a growing movement in healthcare and has been replicated in 75 communities throughout the United States and in other countries, Klass says. Grants and donations fund Nevada’s ECHO effort, one of the earliest to launch.

“Rural residents generally have some access to primary care providers,” Klass says. “If we educate them and share our knowledge, they can become better at treating common but complex and costly illnesses.”

When UNR Med launched its ECHO program, which focuses on topics such as behavioral and mental health and diabetes, it deployed videoconferencing equipment to connect with providers. But that setup was limiting because it required participants to travel to the equipment’s location, typically rural hospitals. UNR Med switched to a cloud-based videoconferencing service three years ago, allowing participants to join consultations or discussions through their computers, tablets or smartphones, Klass says.

Virtual Visits Offer Around-the-Clock Care

Back in Maryland, UMMS operates more than 20 telemedicine programs. Besides ICU services, it provides remote pediatric emergency care in four hospitals, as well as telemedicine services for stroke patients and for thoracic and psychiatric care.

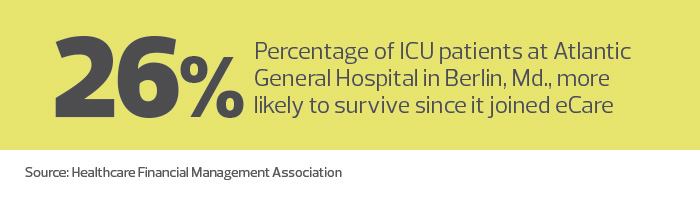

When Zubrow joined the medical system five years ago, one of his first undertakings was to grow eCare, the tele-ICU program, which has served about 90,000 patients since its inception. The 22 staff physicians take turns providing member hospitals with remote ICU services during the night shift, from 7 p.m. to 7 a.m. on weekdays, and 24 hours a day on weekends.

A central operations room at the main medical center campus serves as the program’s hub. It features six workstations, each with two HP Z200 Series computers, eight 23-inch HP monitors and a Logitech webcam, says Irfan Kasumovic, UMMS’s director of telehealth. In the remote hospital locations, each ICU room features a high-end Sony HD pan-tilt-zoom camera and monitors installed above the bed.

On average, the technology helps physicians to remotely monitor 60 to 70 patients a night, although the program can support up to 110 ICU patients.

“We have real-time data feeds, from lab tests and vital signs to X-rays and CT scans,” says Zubrow, who also serves as the director of eCare. “We’re virtually at the bedside and can continuously and proactively monitor patients and fix things fast, so little problems don’t become big problems.”

Electronic health records and other clinical systems integrate with the tele-ICU technology, allowing physicians participating in eCare access to patient information, doctors’ notes and real-time feeds from bedside monitors. Physicians can also log in to secure web portals and connect to virtual private networks through which they can access patient medical images stored on each hospital’s picture archiving and communications systems.

Providing a Remote Pediatric Presence

Tele-ICU has proved so successful at University of Maryland Shore Regional Health’s three rural hospitals and its freestanding emergency department that the provider has expanded telemedicine services to include subspecialty pediatric emergency medicine consultations at all four EDs, as well as palliative and psychiatric care, says Dr. William Huffner, Shore Regional Health’s chief medical officer.

Huffner has teamed up with Zubrow and Shore Regional Chief Nursing Officer Ruth Ann Jones to grow the provider organization’s telehealth programs and improve access for the rural community’s residents.

During emergencies, ER clinicians and patients can now consult with specialists at UMMC’s Children’s Hospital in Baltimore, more than 70 miles away.

Using encrypted, high-definition video and additional technologies, Dr. Marc Zubrow and other physicians can monitor intensive care unit patients at 11 hospitals. Photo: Ryan Smith

Shore Regional Health deployed telemedicine carts in the EDs equipped with a Sony EVI-H100V/W pan-tilt-zoom camera, a computer, a 24-inch monitor and an external Jabra SPEAK speakerphone, which features an omnidirectional microphone and speaker. When hospital staff wheel a cart to a patient’s bedside, they connect to a remote specialist through Vidyo videoconferencing software.

UM Shore Medical Center at Easton, for example, used its pediatric emergency telemedicine capabilities for the first time in mid-March — caring for a 22-month-old boy suffering from seizures caused by a high temperature. Through telemedicine, an Easton physician consulted with a subspecialist at UMMC’s Pediatric Emergency Department to address the child’s immediate health needs and provide referrals to specialists for further testing and care.

“The key is access,” Huffner says. “The sooner and easier the access, the more effective our care is. It allows our patients to get the care from specialists and subspecialists that they need without having to travel great distances. That’s really the measure of success.”

Monitoring Patients in Their Own Homes

Providers also offer in-home care and monitoring through telemedicine. At the University of California, Riverside’s School of Medicine, Dr. Elizabeth Morrison-Banks is assessing whether in-home video consultations with multiple sclerosis patients could one day replace in-person visits. The study is funded by a $100,000 grant.

During the one-year pilot, a nurse practitioner will visit patients’ homes and connect to Morrison-Banks via a notebook computer, cellular wireless connection and Polycom’s RealPresence videoconferencing software.

If successful, she hopes to create a permanent program that allows her and other neurologists to virtually meet with their patients, including rural residents living two hours away.

“If patients can’t easily access their neurology offices, I hope that we can provide that access to them electronically and that it would mean it’s easier and they would be more satisfied,” Morrison-Banks says.

In Arizona, in-home care already makes a difference. Through the past six years, Northern Arizona Healthcare (NAH) has built a comprehensive telemedicine program that spans 52,000 square miles, much of it rural tribal land. Some patients live as far as three hours from the hospital.

NAH offers provider-to-provider and provider-to-patient telehealth services and urgent care visits through video connections. It also has launched a remote patient-monitoring program in which Bluetooth-enabled devices, including pulse oximeters and scales, monitor patients at home.

NAH has seen good results, including a 64 percent reduction in hospital readmissions and an average savings of $92,000 per patient, says NAH Director of Telehealth Gigi Sorenson.

“Patients in the program consistently use phrases like ‘feeling safe in my home knowing that someone is watching,’” Sorenson says.